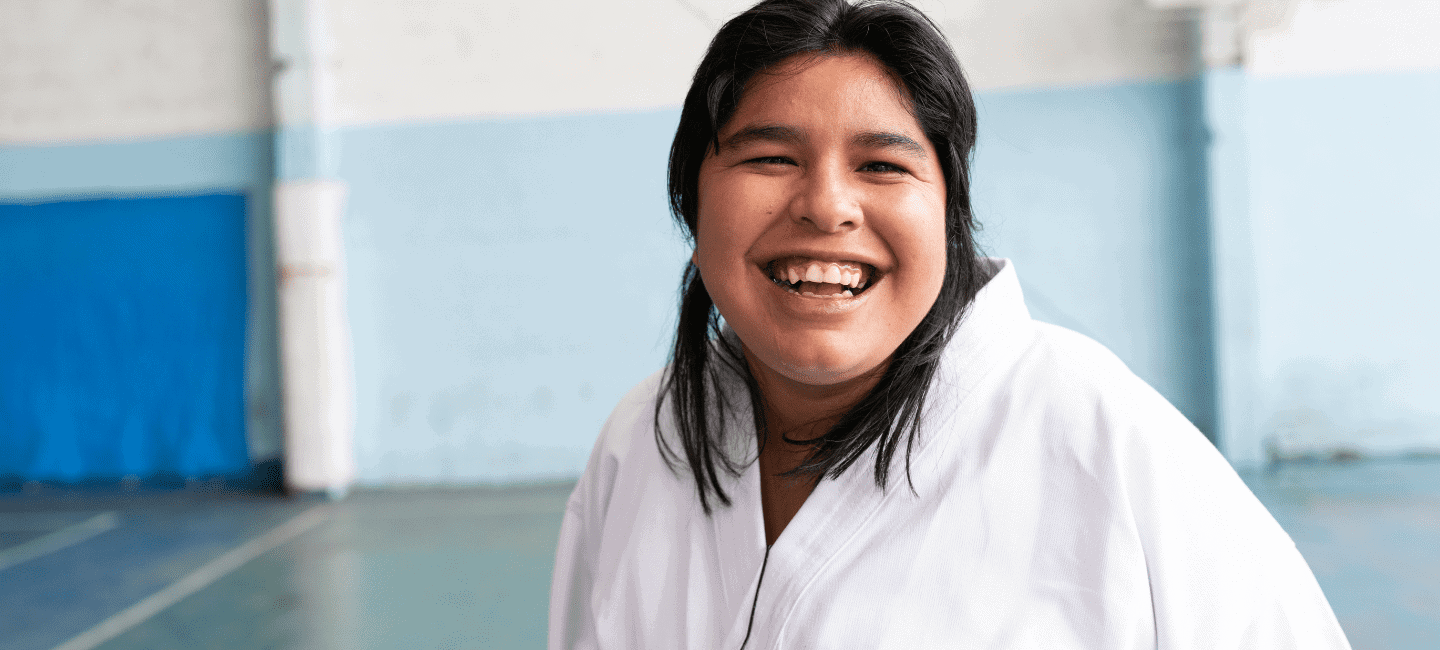

Key Ingredient of High-Quality Transition Programming for Youth with Disabilities

The success of transitions to postsecondary life is significantly affected by the size of transition networks within and beyond the school system, which includes the range of professional roles and services offered, and the effectiveness of the collaborations within these networks.