Addressing Teacher Retention with Discipline-Based Community of Practice

As educators, we need to put more emphasis on creating a balance between gaining proficiency as a teacher and as a subject specialist.

Types of Goals Set by Transition-Age Students with an Intellectual Disability: An Examination

Students often set goals based on teacher expectations. In this study, the implementation of the Self-Determined Learning Model of Instruction (SDLMI) led to students setting a lack of academic or social goals and an abundance of home living goals; this may suggest lower adult expectations for students with significant support needs.

Adjusting Assessment Practices for Students with Learning Disabilities: A Multi-Dimensional Framework for Fairness

A number of factors affect the perception of key stakeholders in relation to the fairness of assessment practices for students with learning differences.

The Key to Classroom Management: Multicomponent Professional Development

Employing effective classroom management techniques can pave the way for positive teacher-student relationships and create a safe space for students to learn, improve behavior, and increase academic achievement.

Leveraging Peer-Mediated Interventions for Academic and Social-Behavioral Gain

The implication of this study for educators is that utilizing peer-mediated interventions, within academic, SEL, and executive function lessons, is once again proven an evidence-based approach to increasing academic gains.

Student Learning Satisfaction in Online Learning Environments and Teacher Presence: Is there a connection?

Just as we develop our students’ self-efficacy and acknowledge the importance of our social presence during face-to-face learning, as the world continues to shift and technology becomes more prominent, we need to consider further enhancing our pedagogical practices for online learning.

Words Have Power: Ensuring language-rich environments for students with autism

Teacher language within general and special education classrooms differs for students with autism, resulting in potentially negative impacts.

The personal and external factors needed for students with disabilities to be successful at university

Identifying these internal and external factors can help universities ensure that they have the necessary resources in place to support students with disabilities.

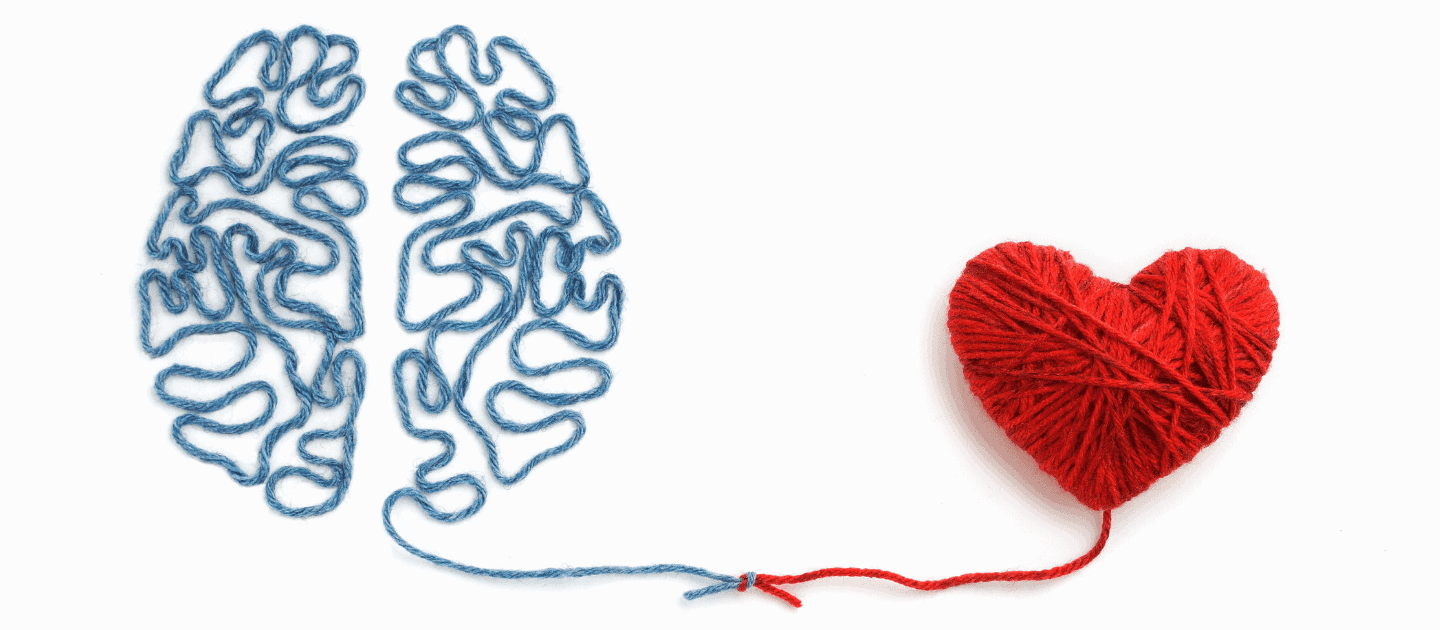

Growth Mindset & Metacognition: A Partnership to Building Self-Regulation Skills Amongst Learners

Metacognitive skills, when paired with a growth mindset, provide complementary skill sets and may be particularly beneficial for students in low socioeconomic school settings.

How does student mindset affect inferential reading comprehension interventions among struggling middle school readers?

As special educators, we need to be aware of how and why students respond to reading comprehension interventions and how attention affects reading comprehension.