Inclusive and emotionally supportive classrooms pivotal in supporting positive student-teacher relationships during school transition

The authors identify that child characteristics, including gender, the ability to self-regulate, and language competence, impact teacher-child relationships.

What Happens After Graduation: Improving the transition to adulthood for young people with autism and additional learning needs

It is imperative that transitions and plans for learners who are diagnosed with autism and needing additional services are put in place in order for them to experience success and independence in their adult years.

What is design thinking and why is it important? – Rim Razzouk and Valerie Shute

The primary purpose of this article is to summarize and synthesize the research on design thinking to (a) better understand its characteristics and processes, as well as the differences between novice and expert design thinkers, and (b) apply the findings from the literature regarding the application of design thinking to our educational system.

Design Thinking for Social Innovation – Tim Brown and Jocelyn Wyatt

Designers have traditionally focused on enhancing the look and functionality of products. Recently, they have begun using design tools to tackle more complex problems…

Metacognition and learning: Conceptual and methodological considerations – Marcel V. J. Veenman, Bernadette H. A. M. Van Hout-Wolters and Peter Afflerbach

This is the first issue of Metacognition and Learning, a new international journal dedicated to the study of metacognition and all its aspects within a broad context of learning processes.

Historical developments in the understanding of learning – Erik de Corte

Erik de Corte describes a progression in which earlier behaviorism gave way increasingly to cognitive psychology with learning understood as information processing rather than as responding to stimuli.

Multifaceted impact of self-efficacy beliefs on academic functioning – Bandura et al.

This research analyzed the network of psycho-social influences through which efficacy beliefs affect academic achievement.

Special Education Laws: Five Important Lessons

Understanding the laws surrounding IEPs within your context will help to ensure that you are able to provide legally sound and equitable programming for your students.

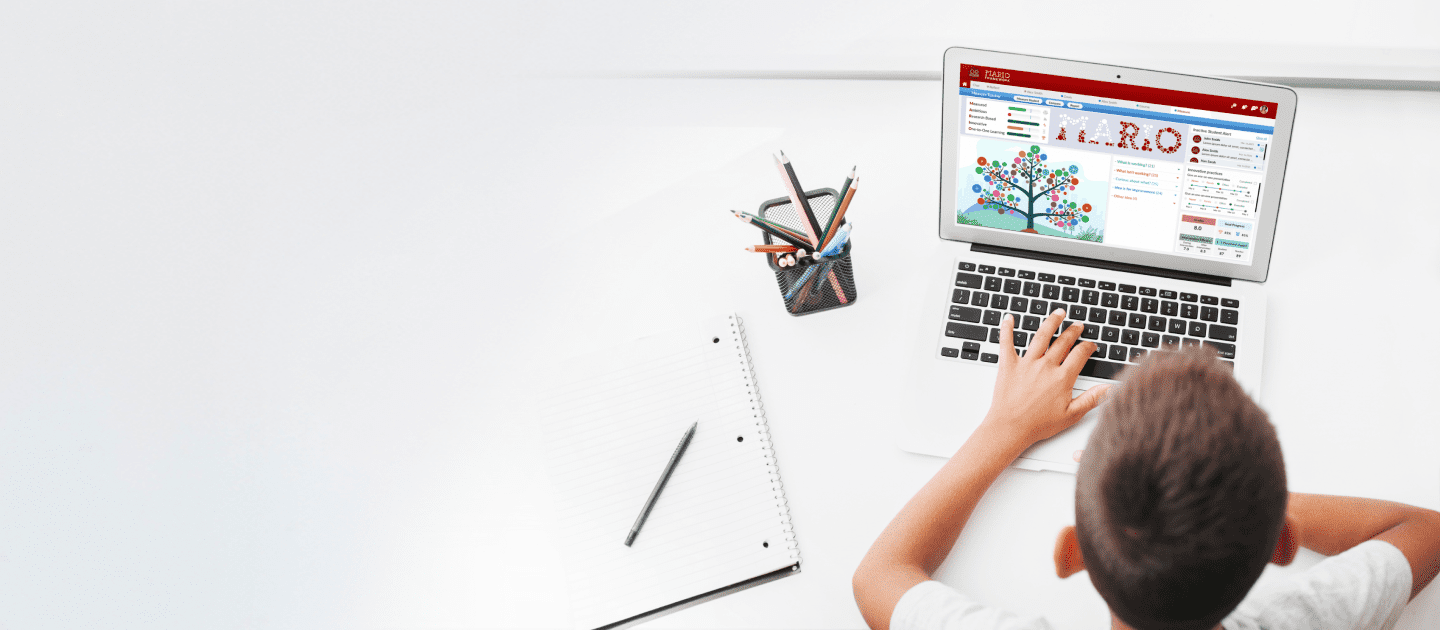

Three High-Impact Strategies for Remote Learning

The shift to digital learning environments has provided an opportunity for special educators to use technology to deliver effective, high-quality instruction. Specifically, substantial research supports the use of Video-based Instruction (VBI) for teaching mathematics to students with ASD.

Do teacher evaluation tools benefit all students?

The authors investigated whether Danielson’s Framework for Teaching (FFT) is a tool which encourages instruction that adequately responds to the needs of students with learning disabilities.