Facilitate positive social interactions for adolescents with ASD with these types of social skills interventions

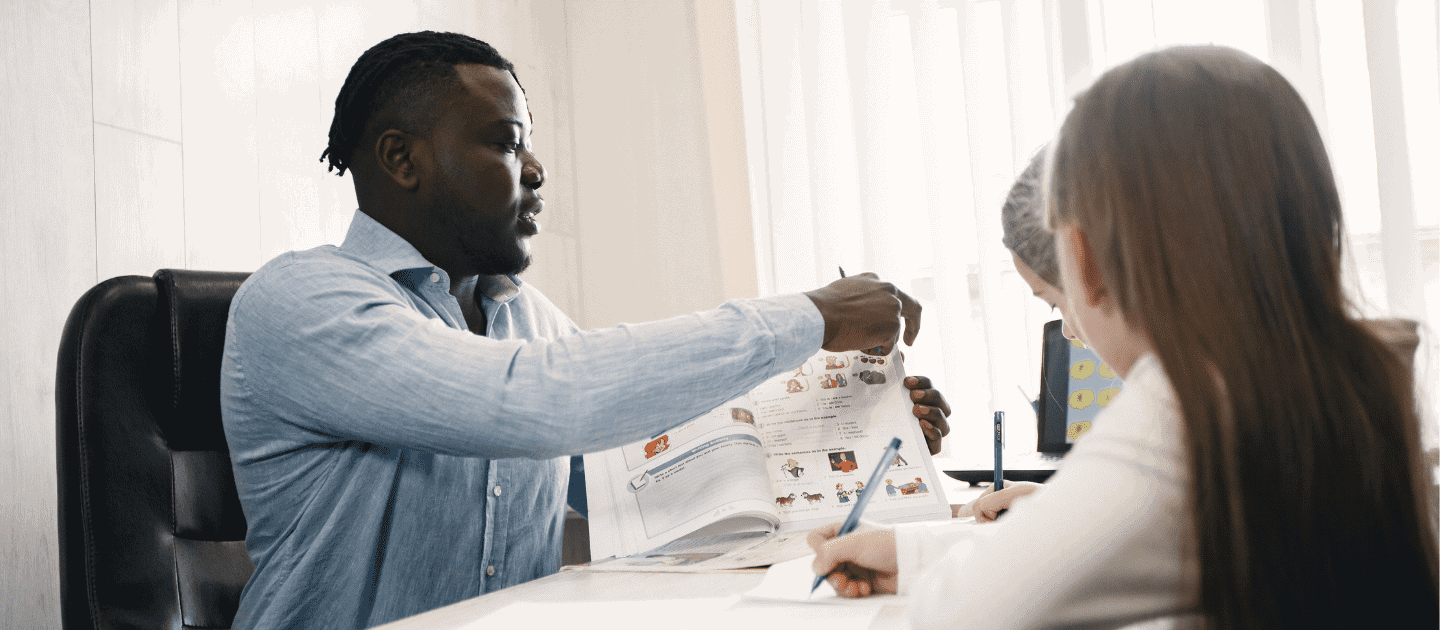

Educators at any stage can provide interventions to both the learner with ASD and to their peers in order to help build and facilitate positive social interactions.

Gaps in the Literature: Interview Training for Transition-Age Youth

Strong interview performances are an essential part of obtaining employment and internship opportunities in today’s society.

Representation, Community, and Disability Identity: A Call to Action

Mueller illuminates key gaps in the present educational system that inhibits disability identity development.

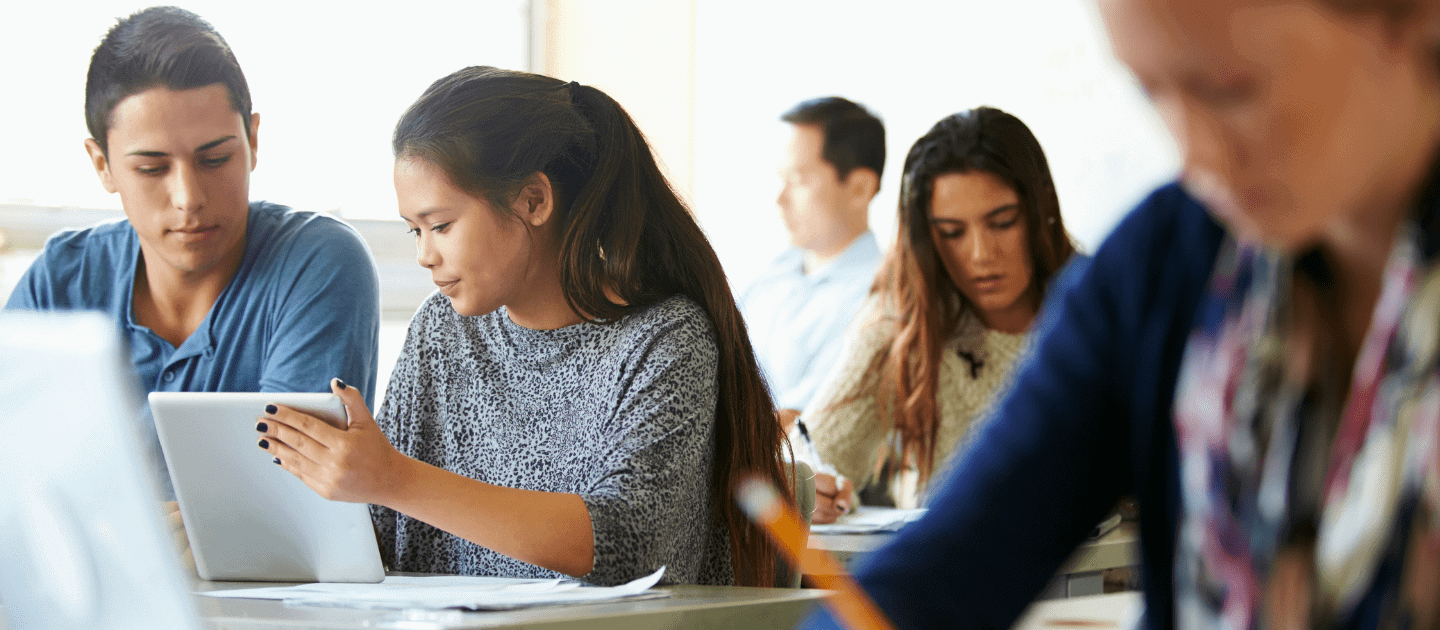

How inclusion through social participation paves the way for special needs students in mainstream schools.

This study suggested that inclusion requires more collaborative learning environments and student-centred pedagogy.

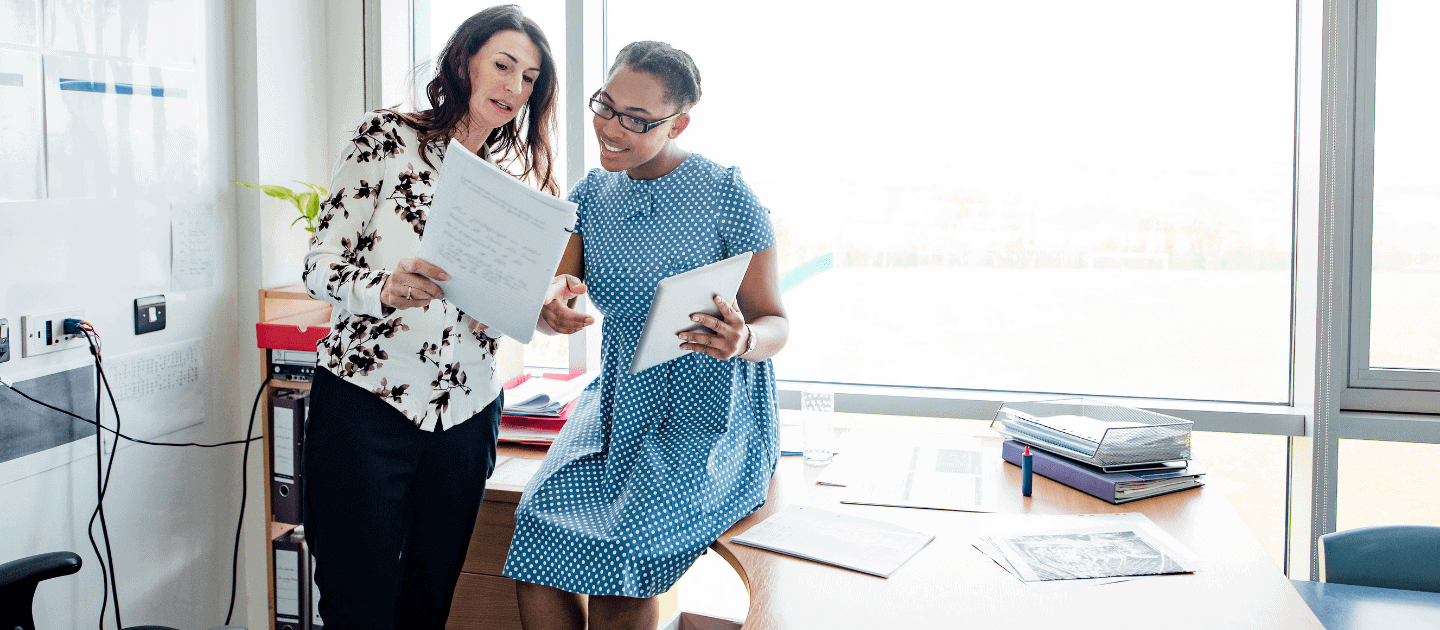

The perspectives of Colorado general and special education teachers on the barriers to co-teaching in the inclusive elementary school classroom

Co-teaching has the demonstrated potential to positively impact the experiences and academic performance of students with disabilities in inclusive classrooms, yet numerous studies have demonstrated that without sufficient training, planning time, or instructional feedback, the potential gains are not consistently realized in practice.

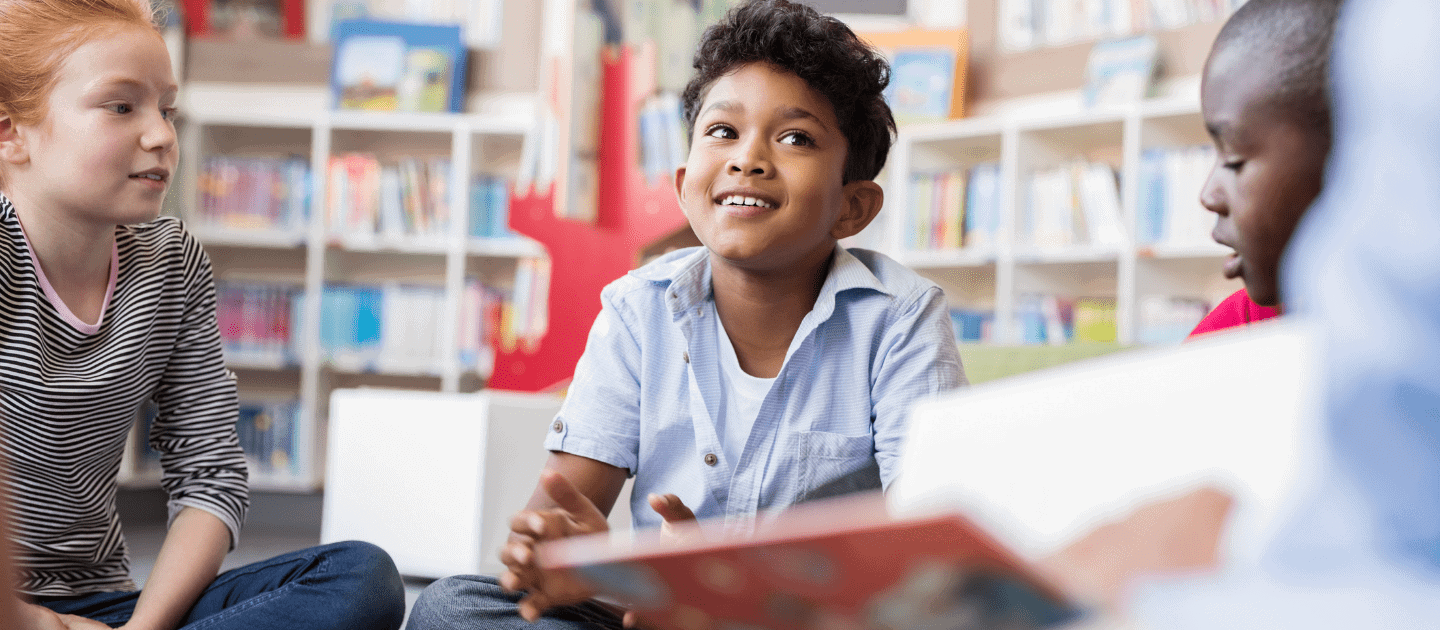

Oral Narrative Interventions: Impact, Efficacy & Implications

Narrative skills play a crucial role in social and academic development, yet prove challenging for students with language disorders.

Can the working conditions of teachers impact student learning?

Special educators who experience more supportive working conditions reported more manageable workloads, less emotional exhaustion and stress, and felt greater self-efficacy for instruction—contributing to more frequent use of evidence-supported instructional practices to address student needs.

The Use of Augmentative and Alternative Communication with Students with Multiple Disabilities

Students with multiple disabilities (SMDs) deserve the right to communicate effectively. One way to meet their needs is to implement Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC), an assistive technology that enhances their inclusion into general education classrooms.

Pedagogical Relational Teachership (PeRT): Reimagining student-teacher relationships to foster equitable participation in classrooms

Key Takeaway: In today’s globalized world, it is imperative that all students are able to use their unique voices and actively participate in conversations. In order to foster meaningful participation in the classroom, educators need to develop strong and trusting relationships with their students. Challenging the notion of what it means to be inclusive provides […]