Balancing Functional and Academic Skills for Students with Significant Disabilities

Students with significant disabilities deserve to (and can) learn academic skills from the general education curriculum along with the functional skills needed to master daily living.

Memory Aids: Trend or Necessity?

Memory aids are being used as accommodations more often than before, and the question of whether they are actually necessary or if they are depriving students of learning effective study and retrieval strategies—leading to an extended dependence on unnecessary accommodations—is arising.

Is Reprimanding Students an Effective Behavior Management Strategy?

Research suggests that teacher reprimands do not decrease students’ future disruptive behavior or increase their engagement levels.

Facilitate positive social interactions for adolescents with ASD with these types of social skills interventions

Educators at any stage can provide interventions to both the learner with ASD and to their peers in order to help build and facilitate positive social interactions.

The Relationship between Reading Disorders and Anxiety in Children

Children with reading disorder (RD) have an increased risk of anxiety disorders, the most common mental health disorder in children.

Supporting Struggling Readers: The Self-Questioning Strategy

In evaluating the intervention strategies we employ with students, we must consider both global effectiveness and effectiveness for target populations, as the success of the intervention may differ depending on the student population it is serving.

The Use of Augmentative and Alternative Communication with Students with Multiple Disabilities

Students with multiple disabilities (SMDs) deserve the right to communicate effectively. One way to meet their needs is to implement Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC), an assistive technology that enhances their inclusion into general education classrooms.

Oral Narrative Interventions: Impact, Efficacy & Implications

Narrative skills play a crucial role in social and academic development, yet prove challenging for students with language disorders.

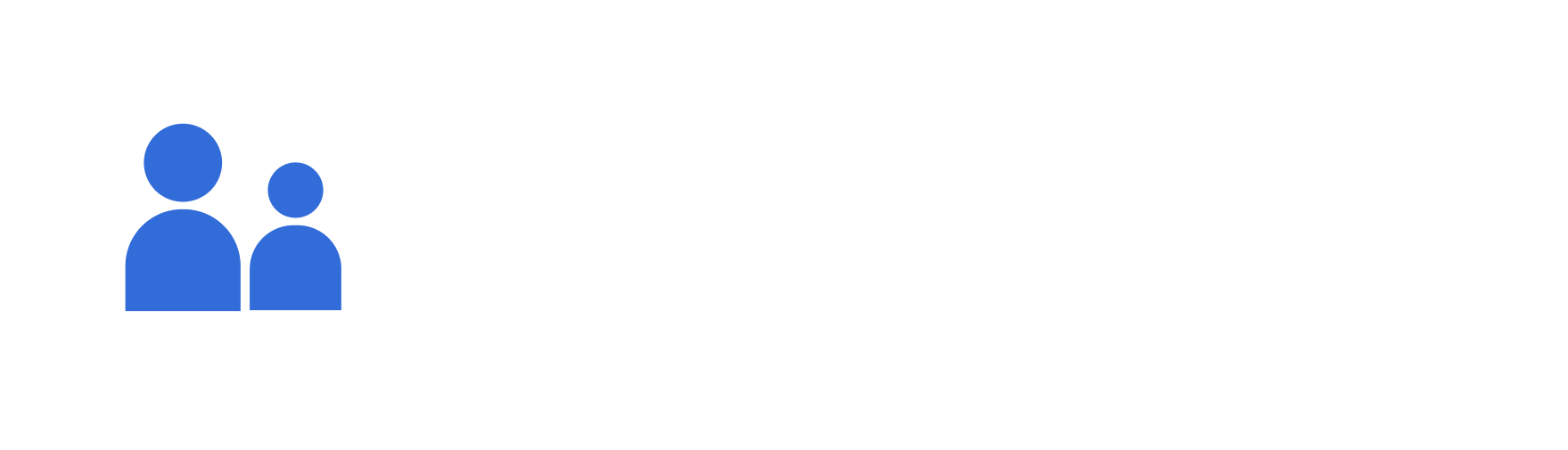

Translating Learning to the Home Environment

Research has indicated that parental training and coaching programmes can be effectively translated into the student’s natural environment.

Can school-wide interventions change school climate?

School climate is a critical component for successful school outcomes. The type of engagement occurring between students, faculty, and the community, the level of safety, and environmental factors all affect school climate.