The Impact of Audio-Support on Reading Comprehension

To compensate for fluency & decoding difficulties, students with dyslexia often receive audio-support.

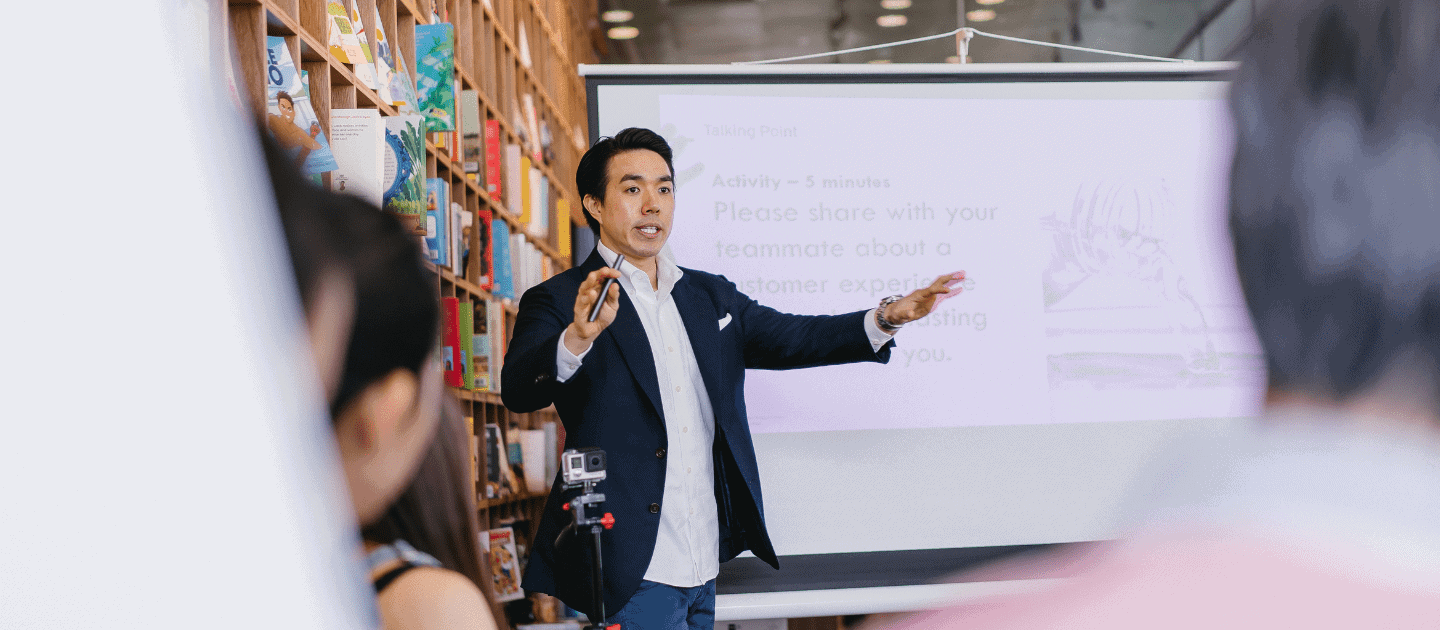

12 Effective Behaviors Used by Early Childhood Coaches

Experienced Early Childhood (EC) coaches whose interactions with teachers were recorded across a period of two years showed a range of coaching behaviors that were consistent with those that have been established as key practices in the existing literature. Analyses of these conversations revealed six predominant themes in the work and beliefs of experienced EC coaches.

Improving Math Achievement for Students Who Are Deaf or Hard of Hearing

Studies show that mathematical performance in d/Dhh students depends more on general cognitive abilities than on specific numerical abilities.

How did special education teachers adapt their practices for students with autism during the COVID-19 pandemic?

As students return to a more normal school routine, IEP teams will have to reassess students’ Present Level of Performance (PLOP) and likely conduct reassessment and revision of IEPs.

The Importance of Trusting Relationships for Students in Higher Education

Having regular pedagogical conversations with trusted peers or leaders can lead to a deeper understanding of their field of study, and in turn to the success of the academic program.

Will mainstreaming and inclusion into mainstream classes lead to better outcomes post-school?

All students should have access to a range of program options that will be appropriately challenging and help them to develop the skills, attitudes, and experience needed to be successful post-school.

Adjusting Assessment Practices for Students with Learning Disabilities: A Multi-Dimensional Framework for Fairness

A number of factors affect the perception of key stakeholders in relation to the fairness of assessment practices for students with learning differences.

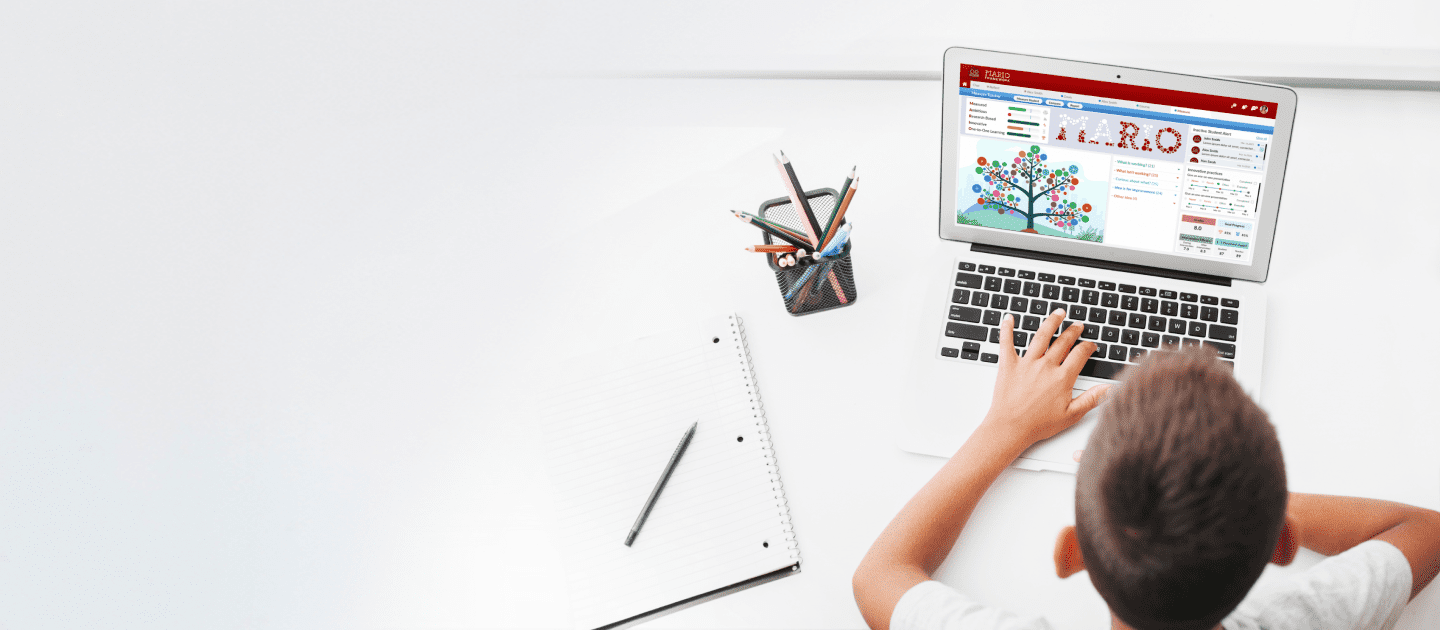

Let’s get connected through personalized learning.

Reflections from students, teachers, and parents in this study show how the personalized learning experience not only produced expert learners but connected members of the learning community, which proved to be a meaningful and valuable experience to all involved.

Will direct engagement with learners change how you provide behavioral support?

The core of personalized learning lies in the direct engagement with our learners through one-to-one sessions and one-to-one conferences. This engagement allows students to connect, identify, activate and be empowered throughout their personalized learning journey.

Multi-tiered systems of support and evidence-based practices – Karen C. Stoiber and Maribeth Gettinger

The purpose of this chapter is to present a combined research- and practice-based framework for integrating a comprehensive MTSS model with EBP, and thus, optimize the results stemming from school improvement efforts.