Clear Roles for Transition Coordinators Benefit All Stakeholders

Though transition coordinators are critical in improving post-high school outcomes for students with disabilities, little is known about their roles and many schools are falling short of their transition responsibilities.

Key Ingredient of High-Quality Transition Programming for Youth with Disabilities

The success of transitions to postsecondary life is significantly affected by the size of transition networks within and beyond the school system, which includes the range of professional roles and services offered, and the effectiveness of the collaborations within these networks.

Transitioning from in-person to online learning during a pandemic: an experimental study of the impact of time management training

In an experiment conducted over two semesters (Fall 2019 and Winter 2020), research indicated how time management training increases self-control and time spent on activities, leading to more academic success. Not surprisingly, however, during the pandemic when time structures dissolved and learning went online, there was an increase in leisure time.

Evidence on the Long-Run Benefits of Special Education

As most education programs focus on short-run learning outcomes, special education (SE) helps prepare students for adult life goals.

Implementing Asynchronous Instructional Materials for Students with Learning Disabilities

As we continue to navigate online learning as a response not only to education evolving but the worldwide pandemic as well, it is imperative that we scrutinize the different platforms we use to ensure that all our students are engaged, supported, and learning appropriate content.

Factors Influencing the Behavioural Strengths and Difficulties in Children with Learning Disabilities

Ayar et al. reveal relevant factors, including socioeconomic status, prenatal smoking, and screen time duration, associated with strengths and difficulties among children with specific learning disabilities.

How can we use ethics of care to understand the transition to adult services for adults with severe intellectual disabilities?

For people with severe intellectual disabilities, transitioning to adult services marks a significant point in their lives. It is during these times and beyond that their involvement in big decisions, such as planning transitions, and the relationships between these people and family members have never been more important.

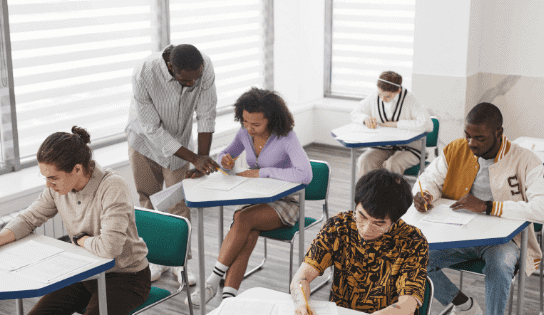

Do teachers treat their students differently?

Teachers sometimes treat their students differently from one another, focusing more on the low-performing students.

Types of Goals Set by Transition-Age Students with an Intellectual Disability: An Examination

Students often set goals based on teacher expectations. In this study, the implementation of the Self-Determined Learning Model of Instruction (SDLMI) led to students setting a lack of academic or social goals and an abundance of home living goals; this may suggest lower adult expectations for students with significant support needs.

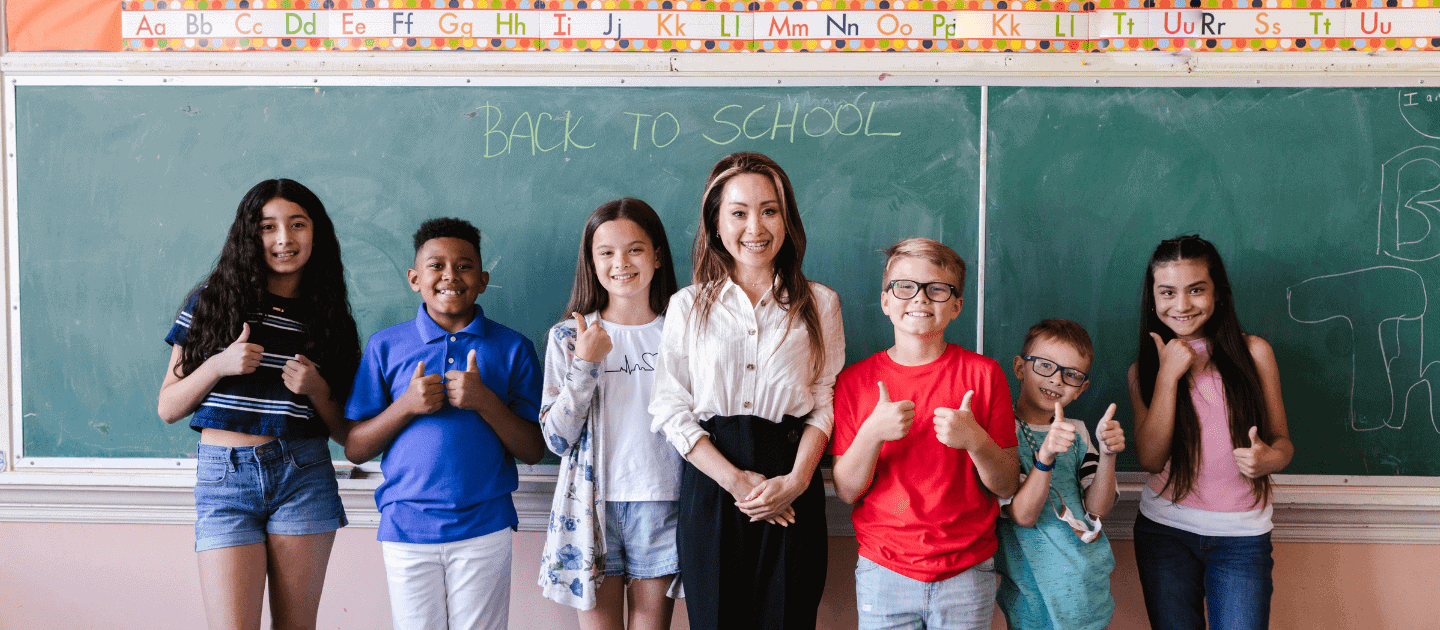

Fostering High University and Vocational Expectations during Adolescence through Discussions

For learners, frequent educational and vocational discussions with friends, family, and teachers during adolescence can be incredibly important in fostering their aspirations and transforming them into reality.