The Moderating Role of Transformational Leadership on Instructional Leadership Professional Learning

Professional Learning While integrated leadership is a well-researched field, most studies focus on its impact on student achievement and often overlook its relationship with instructional practices. This study examines the moderating role of transformational leadership (TL) in the relationship between instructional leadership (IL) and teacher practices, focusing on teacher professional learning (TPL). The Role of […]

The Effect of Learning-Centered Leadership and Teacher Trust on Teacher Professional Learning

Law & Policy, Professional Learning, Cultural Context This study explored teacher professional learning in Turkey by investigating the effects of principal leadership and teacher trust on teacher professional learning. Most existing studies focus on either Anglo-Saxon countries, where schools have held a certain level of autonomy, or East Asian countries that have experienced significant decentralization […]

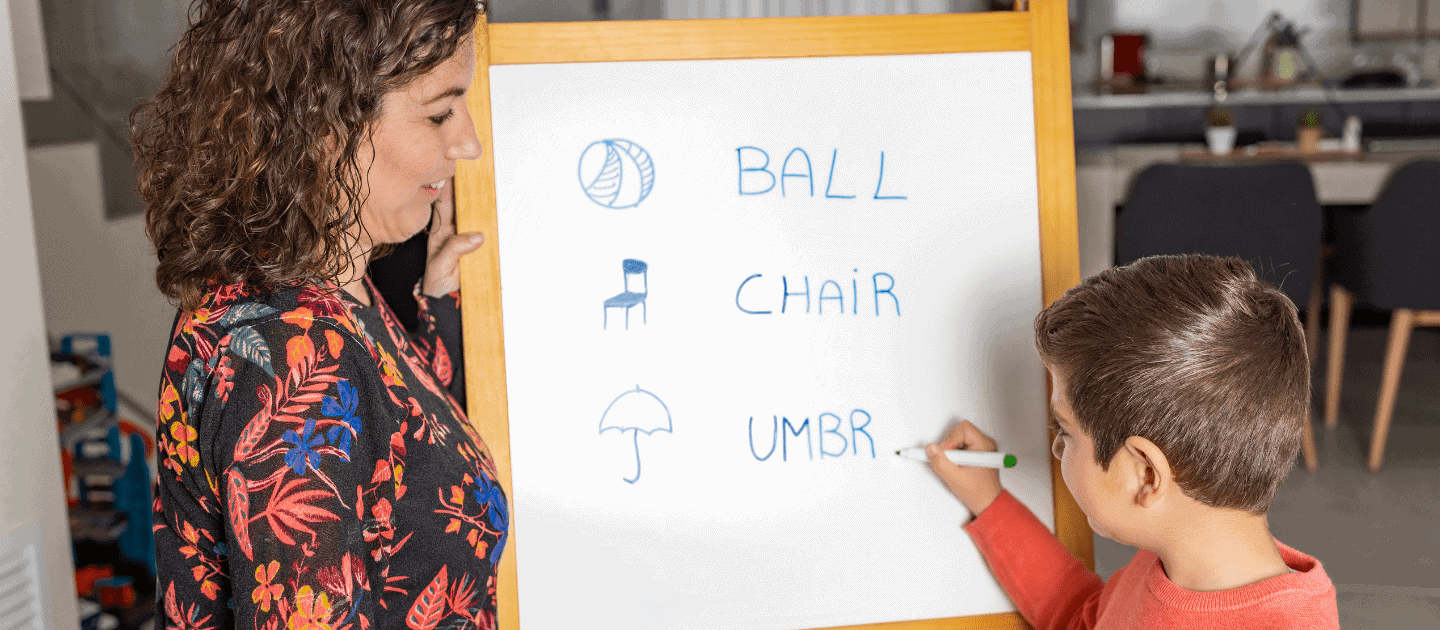

Recognizing and Unlearning Misconceptions in Education

We should be creating awareness of the existence of perpetuated educational psychology misconceptions and the lack of published literature on the effects of the spread of unjustified belief systems in K-12 teaching practices.

Understanding Inclusive Education Among a Triad of Stakeholders

Within American school districts, there is a call to reimagine what inclusive education looks like to respond to the overall need for equity. As a means to initiate this transformation, the study seeks to assess the current understandings of inclusive education amongst a triad of stakeholders (school administrators, special educators and general educators) in order to outline next steps for creating inclusive schools.

How to successfully end your current school year and prepare confidently for the year ahead

When thinking about how to end your school year on a strong note, it will be important to keep both the teacher and student focus in mind for your planning.

The Importance of Progress Monitoring

Common training procedures proved effective for training preschool teachers to collect progress monitoring data, an essential skill for teachers, especially those working within the implementation of multi-tiered support systems.

Empowering SEN Students in Science: inclusive experiences & strategies to enhance conceptual understanding

As educators, we must consider our collaborative planning, teaching, and assessment practices for Special Educational Needs (SEN) students to establish a deliberate connection between their Individual Education Program (IEP) and mainstream science objectives.

How has COVID-19 affected social inclusion and interaction for students with learning disabilities?

While the COVID-19 pandemic created a so-called “new normal” for social inclusion and interactions, particularly in schools where socializing is key for student progress, this study raises the question of whether new means of communication actually improved student efficacy and communication due to the altered norms of school life.

Do Special Education Teacher Personality Profiles Match with the Profession?

A majority of teachers in the study shared an occupational personality that coincided with the Holland Codes of Special Education Teachers (SET).

Closing the Research-to-Practice Gap

Practitioner journal articles are one way teachers can access the most current research and evidence-based best practices.