Supporting the Inclusion of Students with Disabilities in Physical Education: Dismantling the Ableist Discourse

Students with disabilities continue to be excluded from meaningful participation in physical education.

How to fix the research-to-practice gap for students with autism in public schools

Effective teaching and learning for students with autism requires special education teachers to possess a secure understanding of evidence-based practices and how to implement them.

Assessing College Readiness: Are Students with ADHD Prepared for the Transition to College?

The transition from high school to college presents significant challenges for students with ADHD given the reliance on strong executive functioning skills for successful academic performance and independent daily living. However, providing opportunities to develop in key areas such as self-determination prior to graduation from high school, both within educational and home environments, can help to improve college readiness for students with (and without) ADHD.

Science, Technology, Engineering, Arts, and Mathematics Remote Instruction for Students With Disabilities

Over the past decade, we’ve seen a general increase in science, technology, engineering, the arts, and mathematics (STEAM) education as well as making it more inclusive by supporting students with learning disabilities (LD) and/or emotional behavioral disorder (EBD). There are a number of tools and resources available for teachers for maximizing remote instruction to make sure that all students are given equitable opportunities in STEAM education.

Reflective Practice Positively Impacts Professional Identity

Teacher candidates’ perceptions of individuals with disabilities can be positively and significantly altered when exposed to special education content and embedded reflective practice.

12 Effective Behaviors Used by Early Childhood Coaches

Experienced Early Childhood (EC) coaches whose interactions with teachers were recorded across a period of two years showed a range of coaching behaviors that were consistent with those that have been established as key practices in the existing literature. Analyses of these conversations revealed six predominant themes in the work and beliefs of experienced EC coaches.

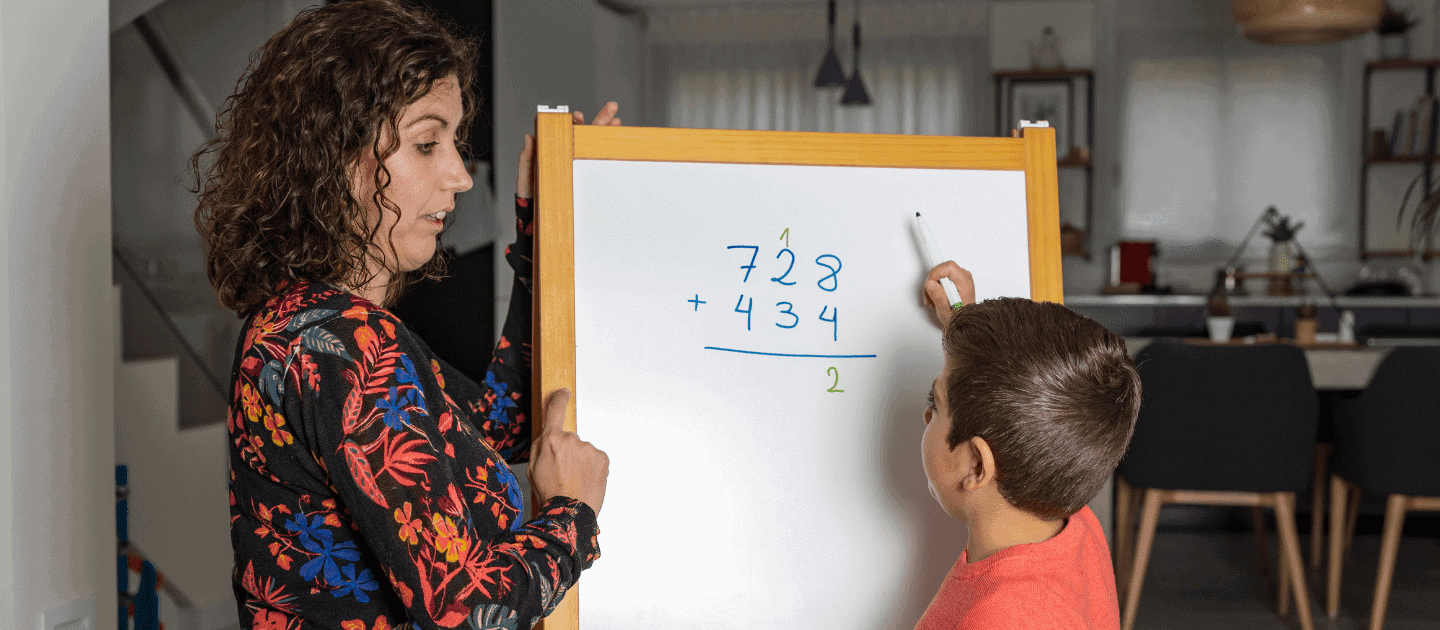

Improving Math Achievement for Students Who Are Deaf or Hard of Hearing

Studies show that mathematical performance in d/Dhh students depends more on general cognitive abilities than on specific numerical abilities.

Supporting Learners’ Metacognitive Awareness

Metacognitive awareness (MA) is a significant predictor of academic achievement, enabling learners to take charge of their own learning by increasing their self-reliance, flexibility, and productivity.

Gaps in the Literature: Interview Training for Transition-Age Youth

Strong interview performances are an essential part of obtaining employment and internship opportunities in today’s society.

Motivation Matters: Three Motivation Strategies to Support Engagement in Mathematics

Elementary students with or at risk of emotional and behavioral disorders (EBD) often experience failure and frustration in mathematics. With high-quality instruction and motivation strategies, such as reinforcing engagement, self-monitoring strategies, and using the high-p strategy, we can improve student engagement and motivation to scaffold learning.