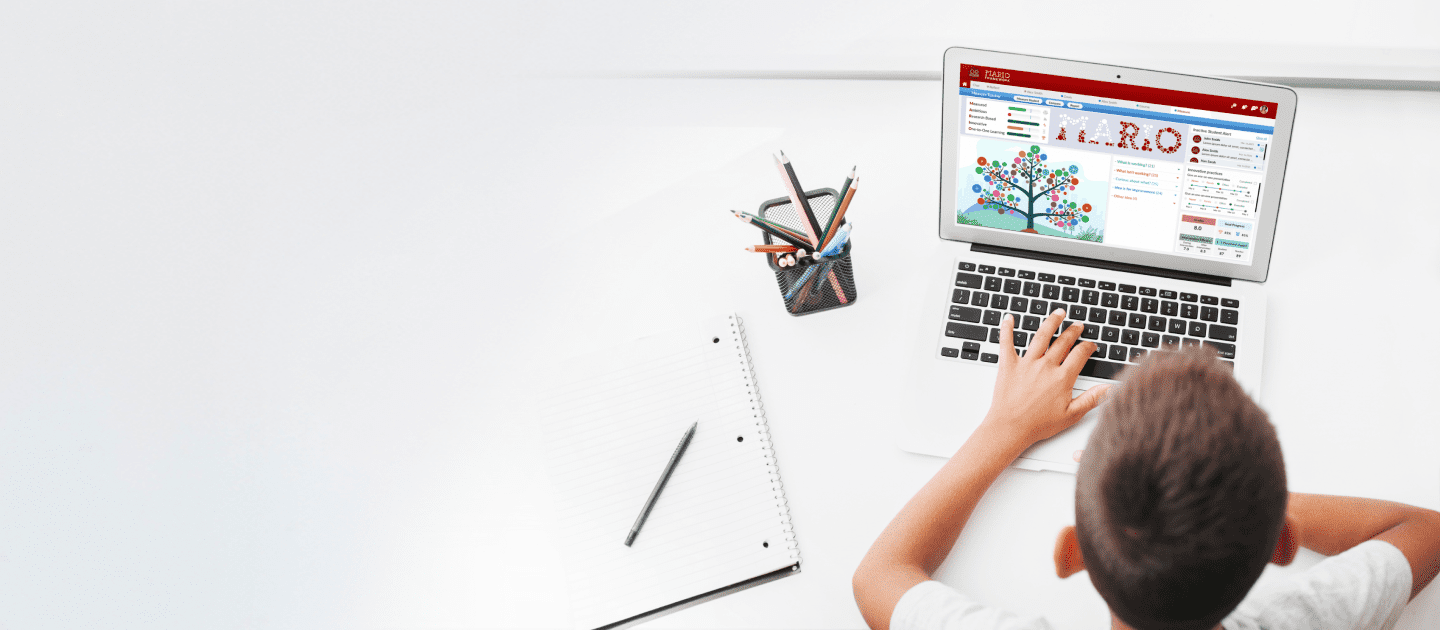

Evaluating the Effectiveness of Educational Games

The authors wanted to specifically examine what knowledge-construction behaviors are exhibited by elementary school students when using serious games and how these behaviors differ across academic performance levels.

Exploring the Dynamics of Self-Regulation, Emotion, and Grit in Student Achievement

Identifying the interrelationships between self-regulation, emotion, grit and student performance by using the Cyclical Self-Regulated learning model, which is associated with a K-12 math tutoring program.

Evaluating Perceptions of Self-Directed Learning in Students

In this article, authors Adi, Artini & Wahyuni (2021) “analyze teachers’ perceptions of self-directed learning (SDL) and the identifiable components of SDL from online learning activities assigned by teachers during the COVID-19 pandemic.”

Pathways to Student Motivation

A meta-analysis of factors which impact student motivation.

Self-Regulation to Combat Mind Wandering During Self-Directed Learning

Mind wandering has the potential to negatively impact the process of learning and has become more prevalent with the increased practice of online learning. Self-regulation interventions may be able to decrease mind wandering and should be widely taught to students.

Tier 2 Behavior Interventions: By the Student, for the Student

When designing Tier 2 behavior interventions, student participation and feedback in the process increases effectiveness as student investment increases with involvement.

Student Learning Satisfaction in Online Learning Environments and Teacher Presence: Is there a connection?

Just as we develop our students’ self-efficacy and acknowledge the importance of our social presence during face-to-face learning, as the world continues to shift and technology becomes more prominent, we need to consider further enhancing our pedagogical practices for online learning.

Teaching & Learning in the Online Classroom: Reimagining Pedagogy to Engage Our Learners

Moving towards learner-centered instruction, well-designed online teaching should encourage students to remain motivated and engaged by providing diverse, collaborative learning activities and creating a space where students are empowered to take control over their own learning.

What is design thinking and why is it important? – Rim Razzouk and Valerie Shute

The primary purpose of this article is to summarize and synthesize the research on design thinking to (a) better understand its characteristics and processes, as well as the differences between novice and expert design thinkers, and (b) apply the findings from the literature regarding the application of design thinking to our educational system.

Historical developments in the understanding of learning – Erik de Corte

Erik de Corte describes a progression in which earlier behaviorism gave way increasingly to cognitive psychology with learning understood as information processing rather than as responding to stimuli.