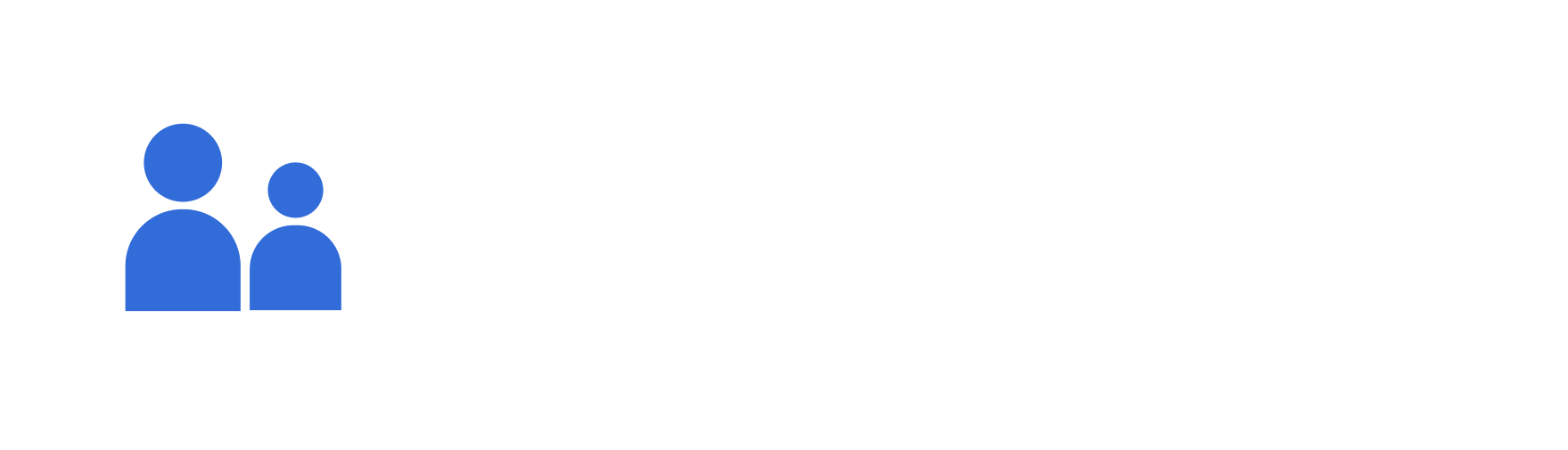

How Culturally Responsive Teaching Relates to Instruction in Schools

Cultural Context, Self-Efficacy The conceptual scholarship on Culturally Responsive (CR) teaching identifies a key problem with its current implementation: schools have taken a “reductionist” approach—reducing CR teaching to a set of instructional practices without considering the crucial aspects of teacher disposition central to CR teaching. Existing studies are primarily small case studies, often focusing on […]

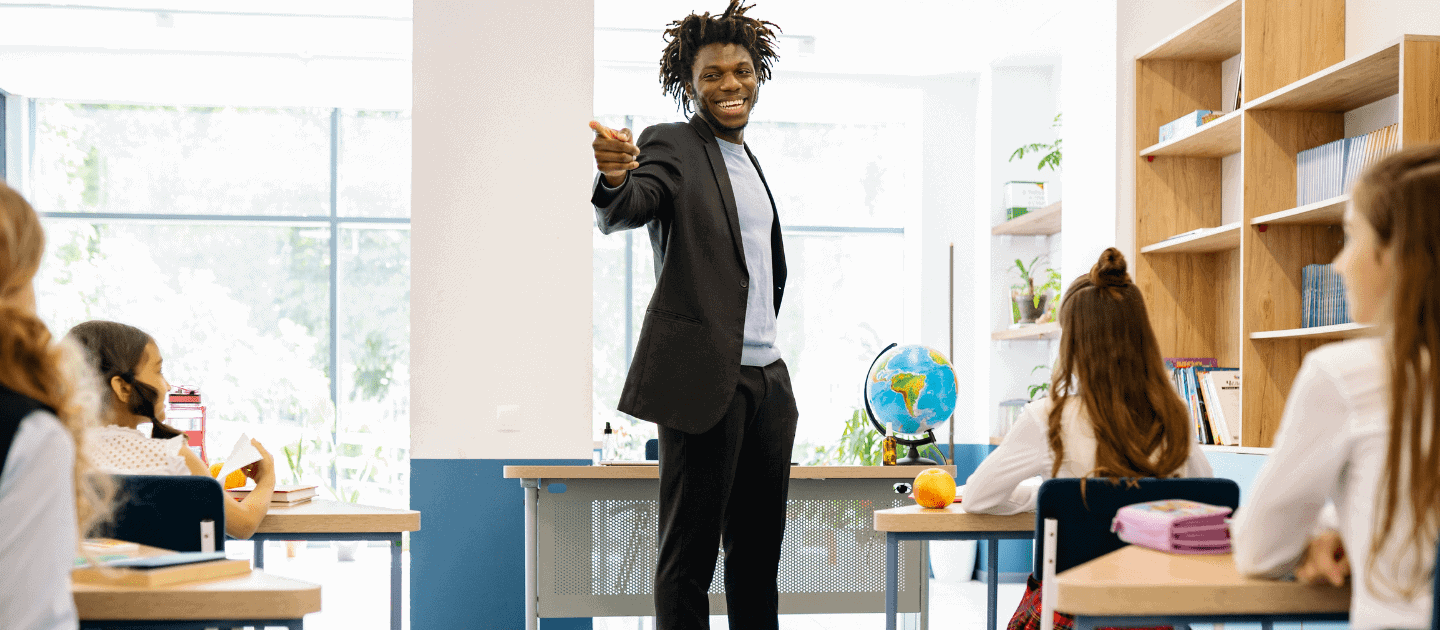

The impact of teacher attitude and teaching approaches on student demotivation: Disappointment as a mediator

Many studies have tried to investigate the factors that reduce the motivation to learn in English. Drawing on the disappointment theory, this study aimed to investigate why and how the discouraging attitude of a teacher and discouraging teaching approaches create negative emotions (i.e., disappointment with English as a medium of instruction), which in turn demotivates […]

Teacher Predictors of Curriculum Adherence

Social and emotional learning (SEL) is necessary for the academic achievement of a student and for their future success in many aspects of their lives.

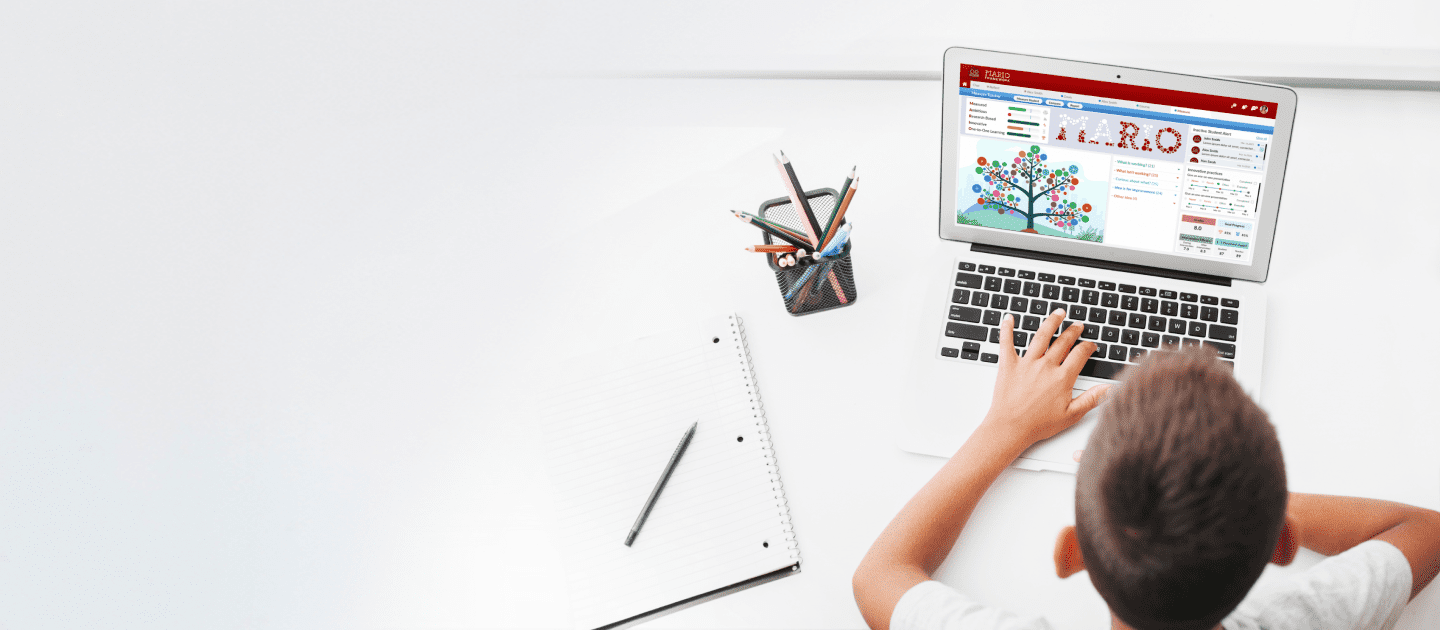

How has COVID-19 affected social inclusion and interaction for students with learning disabilities?

While the COVID-19 pandemic created a so-called “new normal” for social inclusion and interactions, particularly in schools where socializing is key for student progress, this study raises the question of whether new means of communication actually improved student efficacy and communication due to the altered norms of school life.

How can self-efficacy lower the levels of temptation in student learning?

Temptation can hamper engagement and perseverance directed towards a specific task and cause distractions that can impact the learning process of a student.

What is the relationship between memory and self-efficacy among adults with ADHD symptoms?

For students with attention deficit disorder (ADHD) symptoms, their connection with teachers and the memories they have about them later on in their life may predict their perceived social support and self-efficacy.

Teacher Self-Efficacy: A Key Factor in the Success of Inclusive Education

While equal rights of participation of children with disabilities in education is uncontested from an ideological standpoint, the degree to which it succeeds in any context is highly dependent on a number of factors.

Teacher Self-Esteem and Self-Efficacy in Times of COVID-19

The importance of relationships, and in particular those in school settings, is a theme that has begun to come to the forefront in the past year due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Cataudella et al. (2021) from the University of Cagliari in Italy investigated how the pandemic has affected teachers’ self-esteem and self-efficacy while trying to maintain meaningful relationships with their students.

Multifaceted impact of self-efficacy beliefs on academic functioning – Bandura et al.

This research analyzed the network of psycho-social influences through which efficacy beliefs affect academic achievement.

Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change – Albert Bandura

This article presents an integrative theoretical framework to explain and to predict psychological changes achieved by different modes of treatment.