The Effect of Teacher Autonomy and Student-Teacher Relationships on Depression

The number of students with registered disabilities enrolling in colleges and universities across the United States is continuing to increase, speaking to the myriad of improvements and advancements in technology, legislation, and treatment over the past few decades.

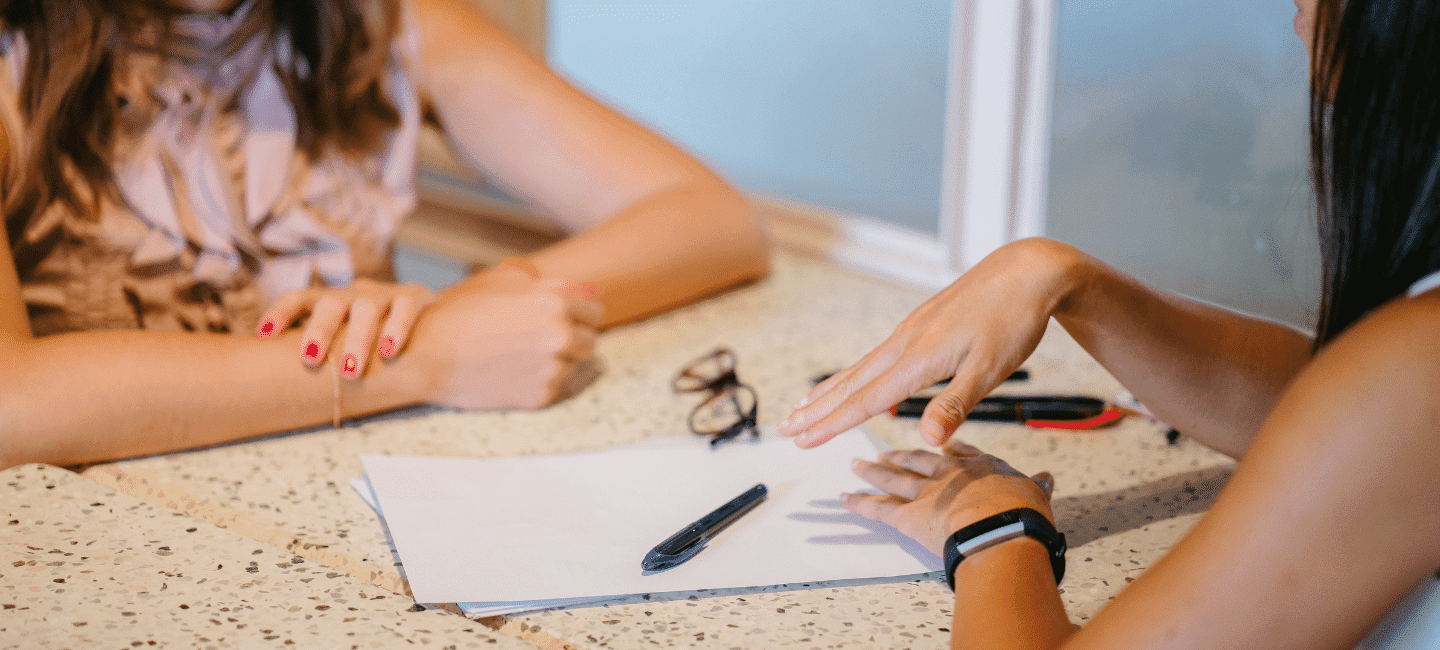

The Effectiveness of Campus Counseling for Students with Disabilities

The number of students with registered disabilities enrolling in colleges and universities across the United States is continuing to increase, speaking to the myriad of improvements and advancements in technology, legislation, and treatment over the past few decades.

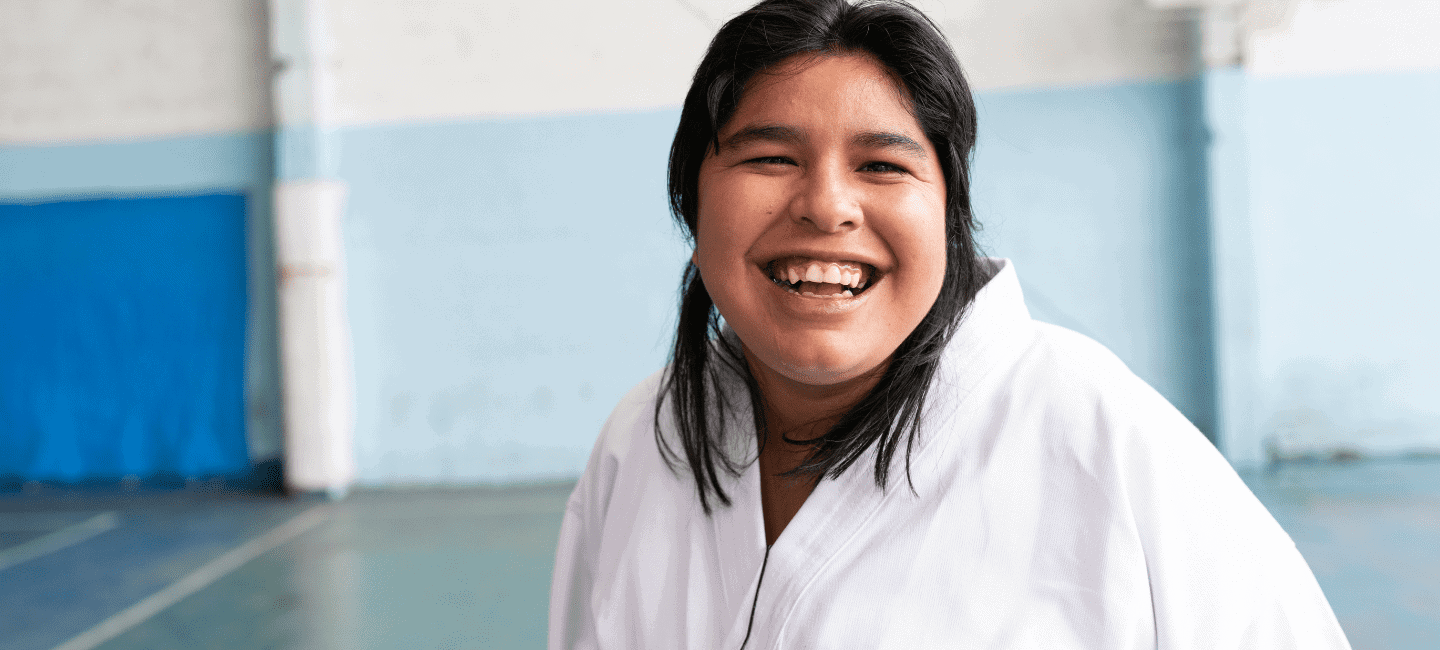

Key Ingredient of High-Quality Transition Programming for Youth with Disabilities

The success of transitions to postsecondary life is significantly affected by the size of transition networks within and beyond the school system, which includes the range of professional roles and services offered, and the effectiveness of the collaborations within these networks.

Evidence on the Long-Run Benefits of Special Education

As most education programs focus on short-run learning outcomes, special education (SE) helps prepare students for adult life goals.